An interview with Drop Nineteens

Frontman Greg Ackell talks about the band's unlikely return, properly reissuing their classic album 'Delaware,' the truth about Winona Ryder, and (possibly) giving Damon Albarn a hernia.

There are not many songs I hold in higher regard than “Winona” by Drop Nineteens. It is an all-time favourite of mine. I can still remember the first time I heard it: late on a Friday night in 1992 during an episode of the Simon Evans-hosted City Limits on MuchMusic. I was recording episodes of that show regularly, so I was able to rewind and watch the video over and over. Like so many songs I heard on that show, I immediately tracked down the band’s CD, Delaware.

(I should add that I was also obsessed with the actor Winona Ryder at the time, so the song title really grabbed me. She was the girl on my wall and I was proud to say that I saw every one of her films up until 1996’s Boys.)

I’m certain I wasn’t familiar with the term “shoegaze” when I first started listening to Drop Nineteens, but they were widely considered the flag bearers for the American bands. The U.S. scene wasn’t as defined as the one in the UK, but there were some great ones making that beautiful noise, like Swirlies, Medicine, Alison’s Halo, Lilys, Majesty Crush, Starflyer 59, Smashing Orange, The Veldt, Loveliescrushing, to name a bunch. But Drop Nineteens had the “Buzz Bin” single on MTV and toured with acts that are now considered legends, like Blur, Hole, PJ Harvey, Smashing Pumpkins and Radiohead, who famously opened for them circa Pablo Honey.

Delaware wasn’t a hit at the time of its release, but in subsequent years it has found a devoted audience that would likely include it atop their shoegaze Mount Rushmore. In fact, as beloved as “Winona” is to the fans, the lengthy instrumental-ish “Kick The Tragedy” has more than double the Spotify listens and seems to be the band’s signature track now. The following year, half the band quit, leaving singer/songwriter/guitarist Greg Ackell and bassist Steve Zimmerman to change course and record the more alt-rock-leaning National Coma. And then that was it.

Like almost all of the original shoegazers, no one was ever really expecting Drop Nineteens to reunite. And that includes Ackell, who spent the better part of 28 years ignoring the fact that he was in a beloved ‘90s band. He left it all behind when he dissolved the band in 1995. But there seems to be something about this current shoegaze movement and its ability to bring bands back. In truth, there aren’t many of them left that haven’t reunited.

Last year Drop Nineteens - Ackell, Zimmerman, Motohiro Yasue, Pete Koeplin and Paula Kelley - returned with their first new album in 30 years. Hard Light felt like a true successor to Delaware, picking up where that album left off. With the vinyl edition of Delaware becoming so in demand, the band are now giving their masterpiece an official reissue. (Order your copy here.) Plus they’ve just announced some dates this fall that mercifully includes Toronto.

I'm always curious about how a band or a musician finds their sound. When Drop Nineteens first got together, do you remember what you were trying to achieve with the music?

There was always an intent with us, it was never meandering. There was always a focus, especially because we didn't play live like a lot of bands, We didn't go around town and play covers; it was all very much about what was gonna go on tape, so that's how we developed as a young band. We didn't really know how to get shows. So instead of sending tapes to all the promoters we sent the tapes to record companies, to the addresses on the back of records that I owned.

But to get back to your question, there were some seminal records at that time in 1987 and ’88, like Spaceman 3's The Perfect Prescription, Isn't Anything by My Bloody Valentine and Daydream Nation [by Sonic Youth] that kind of started it for us. Before that as a teenager I was a fan of The Cure, Echo & The Bunnymen, New Order and The Jesus & Mary Chain - all of that British music. So that's when I started playing a [Fender] Jazzmaster. When we first started doing Drop Nineteens we were certainly going for a sound. I was actually a pretty big fan of the My Bloody Valentine album that preceded Isn't Anything, which was called Ecstasy and Wine. When they first started out they were derivative of the Mary Chain, and I'm not so much a fan of stuff like Geek and Sunny Sundae Smile, which were a little too twee for me. But Ecstasy and Wine had the exchange of those vocals between Belinda [Butcher] and Kevin [Shields] and I just really started modeling things after that and the sound of the guitars. That's really how we started; we were very derivative of that band. At that age you're excited to actually sound like anything, let alone something original. Even if it's derivative it’s very rewarding at that moment in your life. You think, “This could be a thing!”

You formed in Boston, but did it feel like the band was part of any scene there?

Boston really never embraced us. If anything, it was contentious because when we had our first show we already had a Single of the Week in Melody Maker based on cassette tape that 4AD sent them without my knowing. We were in the press before we ever played in Boston, which was a very British thing to do. I don't think Boston liked that, and for good reason. I think they had a legitimate gripe with us.

Our first show in Boston was actually at a very pretty big venue called the Paradise and we were very nervous because we wanted to impress that crowd. They wanted to hate us or at least that's how it felt. And I think that night we were so anxious that we just got really drunk before the show. We didn't disappoint them in terms of letting them hate us. We definitely gave them ample ammunition. But there were lots of luminaries in the crowd that night, like Naomi Yang from Galaxie 500, Juliana Hatfield, Evan Dando, the Buffalo Tom guys, and I'm probably forgetting a few people. But everybody was there. It was intimidating because we looked up to those bands. They were releasing actual records and all we had were these demo cassettes and we really fell apart that first night. But what's interesting is that we recently played that venue again, after 30 years, and it was a nice kind of homecoming actually. A much different experience that we really embraced. This time we laid off the Red Stripes.

You mentioned 4AD sent in your demo?

Yeah, I had a girlfriend living in London at the time. I went over to visit her and we went to shows where I handed out those cassettes to kids. And because I was there I sent them by Royal Mail to 4AD, Creation, Dedicated, Rough Trade, and Fiction, probably a few others. And there was a girl at 4AD named Colleen Maloney and without asking she sent it to Melody Maker and the next week they made it Single of the Week, which was a really big deal at the time. In fact, they had to make up a label name to go with the cassette because they weren't allowed to review demos. I think they called it Pentatonic Records or something. So that kind of got the whole ball rolling for us.

Did you feel any kinship to bands like Ride, Slowdive or Lush who were doing something similar in the UK?

Initially but it was very short-lived because I became friendly with that crowd. The people in Chapterhouse, Ride and Slowdive, they welcomed me and very wholeheartedly. I would stay with them in London when I would go over to do anything business-wise and they were very kind to me. We were embraced by that scene but I still felt like we were outliers and I thought that that was a good thing. I thought, “Let's lean into what we actually are instead of being anglophiles. Let's lean into who we are, which is American.” And I think that's why Delaware sounds the way it does. When all the dust has settled, I guess it's considered shoegaze but when it gets talked about I've noticed that it does usually get denoted as American shoegaze. I wasn't thinking about shoegaze at the time, I think we were leaning into that a little bit more on the early demos, which we abandoned when we got signed to Caroline. When we were making the album we had it in mind to digress a little bit, to stand slightly apart, not above our British counterparts, and carve out a more regionally distinctive sound.

When did you first hear Drop Nineteens described as shoegaze?

I can't remember. The word didn't exist back then. I've seen some press from back then. I was digging through it when we were coming back that I had held on to and shoegaze, the word itself, was not used during that time. I don't know when it first started getting used but what I do remember hearing was NME heard our second demo and called us the “American Slowdive”. This was at a time when I wasn't even that familiar with Slowdive. But the actual shoegaze thing I just don't know.

So Drop Nineteens were always cited as the example of American shoegaze. There are other bands like Lilys, Swirlies and Medicine too, but Delaware is often the album people think of.

I was asked if I perceived an American shoegaze scene at the time and the answer was absolutely not. Looking back I guess there was one, but that's according to history. I mean there was Swirlies. I was friends with Damon [Tutunjian]; we scooped ice cream together at Steve's Ice Cream in Boston together before either of our bands really took off and but we never played a show with Swirlies. The truth is in America we would tour and a lot of times you show up in cities and meet people at shows who would think we were British. But on the on the other side of the Atlantic, they all knew we were American and it served us well because it just was a distinctive strain of a scene that was happening over there.

I remember buying Delaware on CD in the ’90s and thinking, “Why would a band name an album after that state?” I had family in Wilmington who I visited a few times as a kid, so it seemed weird because, well, Delaware wasn’t exactly notable. What inspired the name?

I like the sound of the word. More than anything, that was kind of it. Because it was a phonetical thing. I just love the sound of it, and, you know, it's hard for me to think of album titles. I think there's a girl from high school that thinks it's about her, that it was titled after her, which is fine with me but I loved the sound of it. I remember when I when I told the label I wanted to name it Delaware, they started going through all the albums named after states. Like Springsteen and Bon Jovi. And they were kind of looking at me a little bit sideways. But I think it worked.

Did you ever play a show in Delaware?

I don't think so. We drove through it all the time, but no, I don't think we've ever played in Delaware.

You toured with artists like PJ Harvey, Radiohead, Blur or Smashing Pumpkins. Any particular memories?

There was an interesting trip across the country with Blur. We got along with them pretty well. And as you know, America's a slog. There’s a lot of territory to cover in North America but we played in Canada. And I have one anecdote. At the end of the Whisky A Go Go gig on Sunset in West Hollywood I jumped on Damon's back. We were like 21, 22, and roughhousing, being idiots. When the tour headed to the East Coast after, he had suffered a hernia. I never asked if it was my antics of jumping on him that caused it but I did notice he was a little less friendly after that. So I've always had this suspicion, this foreboding feeling that maybe I took him out. He was relegated to singing on a fainting sofa. But it was good for him to do that instead of canceling the shows.

I’ve always felt that “Winona” was the best example of how shoegaze could produce a great pop song. Did it seem like the band had achieved something special?

I knew that we had something in that song, but there was a big debate about the mix. At the time there was a big fad of having these songs that went soft to loud, which I guess Nirvana had a lot to do with. What I really wanted on that song was for it to be more condensed sounding and dense sounding, where instead of it being very dynamic it would start and it would go and it would stop. It wouldn't have have hills and valleys. It would be the guitar melody that I'm playing, and then my vocal line. I wanted those two melodies to run through this dense thing, like ribbons. That's what the goal was and I had to struggle to get it to sound like that. I ran into trouble with the co-producer and had to try to steal the 2” tape and go do my own. In the end our label accepted my mix. We weren’t reaching for the stars on that one, but yeah, you're absolutely correct: it's a pop song.

I talked to Kevin Shields about that song once and he said to me, “I love that song. I just like how it just kind of goes along.” And that's all he said. But that's exactly what I had intended for it to do. So to hear that from him was quite something. I thought that was a triumph in my mind but it is a pop song and I don't find it very gazey. I think if anything, we stole the beat from Galaxie 500, who I don't consider shoegaze. They’re sort of a deconstructed kind of rock outfit. So there there's aspects to it that I was definitely pulling from. It's not waves washing over you, it's a steady kind of propulsion.

I’m sure you’ve been asked this a hundred times but is there any correlation between “Winona” and Winona Ryder? In the ‘90s it was hard for me to separate the two. I feel like that is a common theory.

I dated a girl who played her sister in a movie called Boys and I was a fan of Winona’s, but it's not really a song about her. She features in the song, but it's really a song about Drop Nineteens. It's an odd thing to write a song about your band before you've even really started or as you're starting out, but there were things in there that were proved true to this day. A guy who does that stuff really well, that sort of self-reflective songwriting is James Murphy from LCD Soundsystem. His lyrics are kind of elliptical like that, and I think that’s something that has always interested me in writing lyrics. Certainly when we came back for Hard Light, a lot of the lyrics were kind of like that.

Personally I was a bit surprised to see “Kick the Tragedy” had more than twice the amount of streams as “Winona.” It’s funny how those things happen.

I remember having a discussion about “Kick The Tragedy” with Keith Wood at Caroline, who signed us. We were talking about the sequencing of the album and he realized that “Kick The Tragedy” was essential to the record. That song was a bit of an experiment and more than a song really. It has taken on new life though and gotten more attention over the years than then it did at the time. We never played that song live. It was not central to this band. And now having come back, if we don't play that song they will burn the fucking house down. They all know it's coming, and honestly we have to play it last because if we played it anywhere else in the set people might leave early. That's our fear now because it's beloved by the people that care about us, so we had to figure out a way to execute live. It took time to kind of realize and recognize it. We're not the first band to talk in a song but it kind of works, and there is something about that bass line. That's the little secret in that song because it really pulls at your heartstrings. It’s kind of telling its own story and that's credit to Steve.

One of my prized possessions is an original vinyl copy of Delaware, which has always sold for big sums of money. Was that something you were aware of as sites like Discogs became more popular?

I wasn't aware of anything. I think some of the other band members were but I didn't even have Spotify until this year. I just wasn't interested in streaming services and I would never Google our band’s name. I was kind of afraid of what I'd find, honestly. That's just my nature. But I found out about it and it annoys me. People just want to have something in their hands, and they care about that record. That's very flattering to us, but it shouldn't require you to empty your 401k or your college fund to buy it. So that was one of the reasons we agreed to do this reissue with Wharf Cat, to get it into people's hands at an honest price. We weren't able to afford putting anything else on it - it's just the album. So we did remaster it for the sake of modern hi-fi and there are things you can do now to make it a little bit better standard. But we didn't change anything about it other than the artwork… which you're probably gonna ask about.

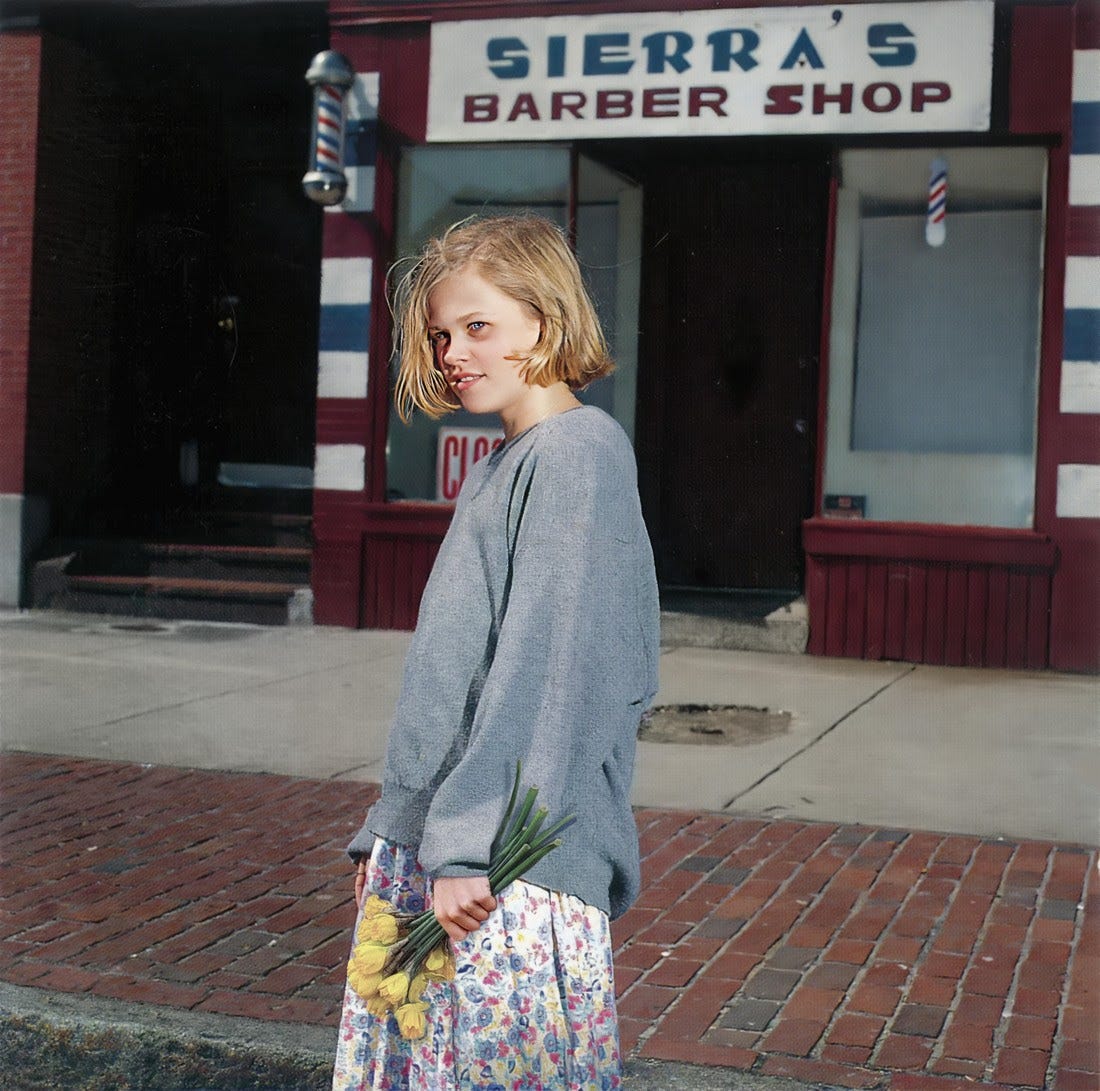

Right. You decided to replace the gun with flowers for your reissue’s cover.

You've probably read about it, but the feeling was if we're gonna put that out we weren't gonna put that image out for anyone to make money on in this climate. I don't regret doing it at the time. In my opinion putting a gun in a young person's hand was even overstated at the time, but it was my concept and I stand by it. The same way that I stand by changing it. It's our album and if people feel that's a violation or they just love the real cover and they feel we shouldn't have changed it, well… we're donating our cut to charity to Artists For Action To Prevent Gun Violence. It’s a great cause and we're doing our bit and we're saying what we want to say by doing that. People can have whatever opinion they want, it's fine with me.

I’ve always liked the cover, but for me it was just an album cover from the ’90s. I never thought much about it when it came out. I think I would feel differently about it though if it was released today. And I feel the same way about Dinosaur Jr.'s album cover for Green Mind, which has that young girl smoking a cigarette. I’ve always liked the image, and I’ve owned that T-shirt for the last year 20 years. But now I avoid wearing at times because the idea of someone that young smoking now really repulses me. I might wear it to a concert but I wouldn’t wear it to my daughter’s school concert.

For me, it's not that it's dated and I don't think I'm correcting a problem. I'm just doing what we want to do now. I'm not trying to erase that image. In fact, it will still be on streaming services because we don't even have the rights to it. So when people stream the album it's still gonna have that image. But if we're gonna put a product into the marketplace for people to spend money on I don’t want that gun in the girl's hand. It's just that simple. We do realize that some people have a a connection to that cover; it has taken on a life of its own. By a certain measure it's a very successful album cover. Like there was a collaboration with Jerks, who did some clothing and a skateboard with it. I do think changing the gun to daffodils was smart and tasteful and cool. We're all fully behind it.

Music On Vinyl is also reissuing Delaware with the original cover. I’ve spoken to other bands that had their albums reissued by that label without their permission. I don’t think they’ve received any compensation from it either. That must have really messed with your plans. When did you find out about that?

We found out about it because we were doing our own thing with Wharf Cat. And it was a real process getting Universal Music Group to issue the license to Wharf Cat to do the reissue on vinyl. In fact, all of the band had to sign off on it. They literally needed our consent for this whole thing. But as they were doing it they found out about the other reissue. I don't know who told me but it was news to everybody. What I don't understand about it is how they needed all of this consent for our approved remaster, but they didn't need anything from us, they didn't even notify us for the other one. And like I said, I'm not putting that cover out there for people so the band could make money off it. So that bothers me. Number one, that we weren't consulted. And number two, that even if they had the rights to do they didn't even tell us about it. It's obscene really, but I guess the rights are what they are. What are you gonna do? Except do our own thing and then tell our audience to the extent where they can say, “Hey, we don't have anything to do with that one, but we have something to do with this one.” We're not even gonna make money from ours, so it's not like, “Don't buy that one because we won't make money from it and we'll make money from this one.”

We went on a small string of dates and there were a lot of people that lined up before and after the shows trying to get stuff signed by us, which I wasn't anticipating. It was mostly young people too. But we were signing a lot of things and every now and then a few people would bring that reissue with them. So I did have a few of them in my hands and it looks fine. I did sign it for them, but I told them, “I'm doing this because you're a fan and I'm assuming you didn't know any better.” And I’d tell them that we have our own version coming out and hopefully people will buy it. Hopefully it's actually a little cheaper too.

What are your feelings towards National Coma these days? It’s such a different record.

Well, it was a different band in a lot of ways. Steve and I were the only members then; the others left after Delaware. We were just trying to find our way. Delaware was a departure from the demos, and we felt that this was just something that interested us, to keep evolving. But I think Delaware was an improvement on the demos and an improvement of the band. And I'm not a big fan of National Coma now, but I understand what we were going for. I'm responsible for that stylistic left turn. I was at the wheel of this band and I was reaching for something there. I'm not torn about it now. But I recognize we disappointed a lot of people with that record, which is too bad but we were doing our thing, trying to be creative and give people something they didn't expect. That's the way it goes sometimes.

One of the one of the reasons we came back to do Hard Light was to follow up Delaware in a way it deserves to be followed up. I don't think Hard Light sounds like Delaware but I do think it has a connectivity to it that sounds like it could have been the next record back in the day. Something that could be more favourable than National Coma.

You mentioned the demos, which were pressed to vinyl and sold exclusively at your shows. Will you be giving that a proper release? They sound amazing.

That was a record company thing. That wasn’t us. In order to get the vinyl made to sell we had to agree to not stream it right away and wait to sell it online. I didn't like the agreement. My idea was to put it out on streaming and then maybe sell some vinyl at the shows. What we don't have is the money to invest in making these records available to people. But yes, the plan is to get it on streaming and make [the vinyl] available online to buy at some point. It's just unfortunate that people have to wait, and the reason for that is a little bit out of our control.

So about the reunion. How closely did you pay attention to the band’s following over the years? When did you realize that a reunion just made sense?

Honestly? Not until we played these shows in April. Sure, we got a lot of press attention after announcing we were coming back and the reviews of Hard Light were really good across the board, so I knew that we were back in the conversation. I didn't know that would be the case. For years the understanding was that I wasn't interested and they were right about that. But in any case when we finally came back it was irrespective of whether it was gonna make sense or not. I wrote a thing on Twitter and said, “Hey it's Greg from Drop Nineteens and I'm gonna make this fucking record.” At that point I had no idea. I didn't even know how to look at Spotify numbers. We could have done this and there would be no reception for it. So when we got the critical acclaim for the new album and doing interviews and we were in the conversation clearly.

Then I didn't know what the shows would be like. I didn't know what the makeup of the crowd would be. I didn't know that they'd be full of people. The day we announced that every show sold out was really an education for me to get out there and play in front of people. To see what was gonna happen. Let's put it that way. So that's really when I realized, “Hey, there is an audience for us and this is a viable thing to do.” Even if coming back hadn't worked out that would have been okay too. But it feels good. It'd be a shame to squander the work we’ve done. There a still lot of people out there that haven't gotten to see us in cities that want to play so we're gonna keep this going.

I was so happy that Hard Light was as good as it was. Because as a fan you never know what it’s gonna sound like when a band gets back together after such a long period. How hard was it for you to get back into songwriting?

Well, as the story goes, when I decided to do this I reached out to Steve, who’s basically my songwriting partner, and said, “Okay, what would a modern Drop Nineteens single sound like?” At that moment he realized immediately that we're gonna do this because he had been waiting for years for me to say that. I didn't even have a guitar in my apartment in Brooklyn at the time. I had some in my farmhouse in Connecticut, which I’ve now sold, so Steve overnighted me a Fender Jazzmaster. My girlfriend was on her way to Miami so I had the apartment to my myself and sat with playing that guitar over the course the long weekend. When she got back on Monday I had written like my the lion's share of that album. I hadn't picked up a guitar in about 20 years!

In terms of my artistic life, when something's over I put it down. And I was very finished with music and content with that. No regrets about it. But I was surprised I could even play but the chords started coming out. It was a surprise to me more than anybody that I had anything to offer but I did. If you make music and you're not actively doing it I guess stuff piles up.